- Published on

On Surrender

- Authors

- Name

- Maa's Beloved

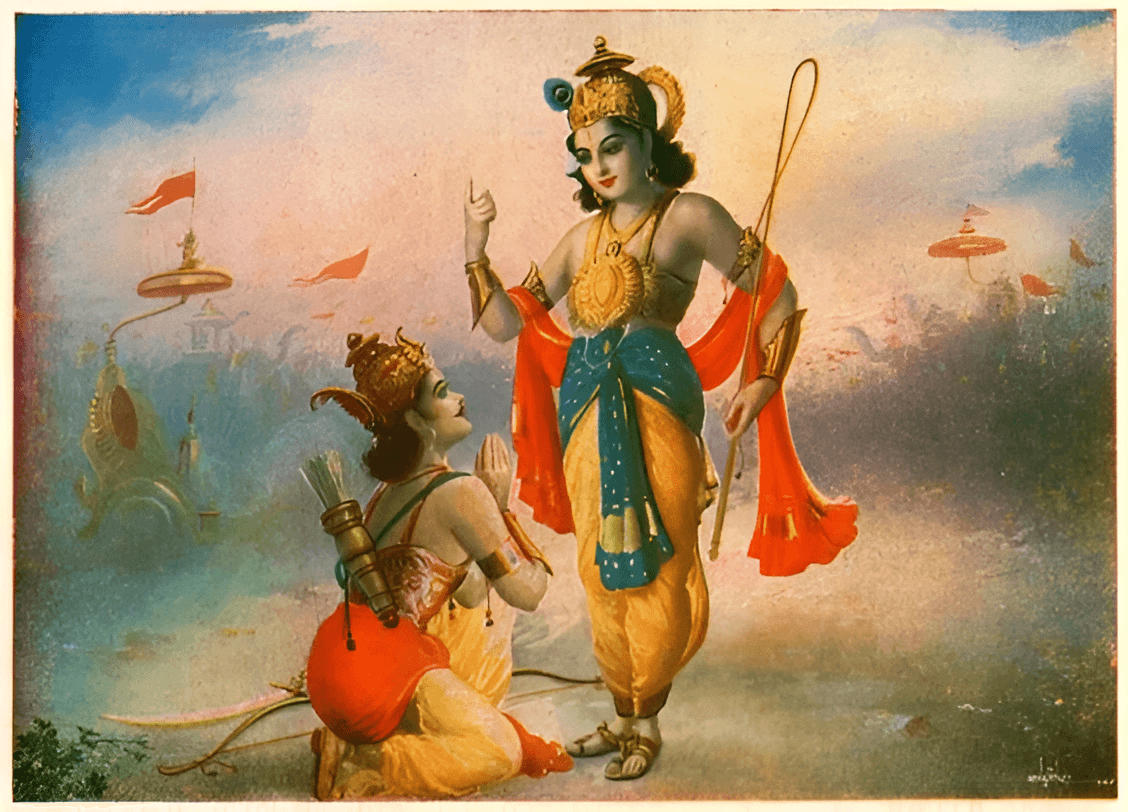

Across many traditions, the ideal of complete surrender is seen as an essential aspect of spiritual life. In Bhakti Yoga, the goal is one-pointed devotion, cultivating an intense longing for the Divine, next to which all other attachments fall away. In Karma Yoga, the goal is the complete renunciation of the fruits of action, so that every deed is done purely as an offering at the feet of the Lord. In Jnana Yoga, the path begins with vairagya, a deep dispassion for worldly things and the single-minded pursuit of the True and Eternal. The philosopher Kierkegaard says, “Purity of heart is to will one thing.” Jesus Christ teaches, “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will save it.” Lord Krishna declares, “Abandon all dharmas and take refuge in Me alone. I will deliver thee from all sin and evil, do not fear.” The common thread in all of these paths or teachings is this movement in which all that is—the self, all it considers its own, all its desires, all its conceptions of what is or how things should be—all is surrendered as a complete offering to the Divine. In this movement, the soul can say with complete sincerity, “I seek nothing but You, Lord. Grant me only pure love for Thee. Let my actions in the world serve only to glorify You and to bring about Your will.”

Before spiritual life becomes a manifest part of our lives, when we are deeply engrossed in the world and its pleasures, the idea of surrender seems irrational. Why should I give up what I want for something else? But things begin to change when we become conscious—however faintly—of some truth, ideal, or essence that transcends or encompasses all our other concerns, desires, and attachments. Plato speaks of the Good, “which every soul pursues and for its sake does all that it does, having an intuition of its reality, but yet baffled and unable to apprehend its nature adequately, or to attain to any stable belief about it as about other things.” In the Hindu tradition, God is described as “sarva mangal mangalyai”, the goodness in all that is good. When we first get an intuition or awareness of That which is the source of everything we long for, we begin to finally see within us a developing impulse of surrender. In the growing spiritual aspirant, however, this impulse has not yet fully blossomed. It is often obstructed by fears, attachments, other commitments, and aversions. Though part of us longs to “will one thing” and offer our entire being to God, another part still hesitates, holding us back. This tension characterizes the condition of the budding sadhaka or spiritual aspirant. We stand at the edge of the cliff, peering into the chasm, longing to make that leap of faith, but we still glance back over our shoulders, unable to fully give ourselves over to the Divine.

Through my own struggle with surrender and conversations with many friends, I have found several examples of fears or thought processes which create within us this aversion to surrender. In almost every case, I have found that this fear seems to arise out of some kind of confusion or misunderstanding about the nature of the surrender asked of us in spiritual life. In this writing, I aim to explore some of these aversions, trace their root causes, and use careful discernment to expose the contradictions hidden within them. In doing so, the hope is that as our fears are quelled one by one, we may feel more ready to make the movement of surrender. Ultimately, there will still be a leap of faith we must take—no line of reasoning can make that jump for us—but these reflections can be seen as preparatory movements for that complete surrender. May all this be an offering to God who resides in the hearts of all beings and in whom we all reside, who is the reservoir of all that is Good and the ground of all existence. May this serve to bring all closer to the Divine.

The Fear of Missing the Highest

The class of fears that I have found most commonly, especially among spiritual aspirants, is a fear of in one way or another missing the Highest. In my own experience, this fear was of a wrong or partial / incomplete understanding of God leading me astray (see To the highest). The concern was that if I engage in a complete surrender before knowing precisely who I am surrendering to, or without complete certainty that the surrender is to the Highest, I might unknowingly surrender in the “wrong” direction and be led away from the One who I truly long. For another friend, this fear manifested as one of surrender leading to a kind of idleness—either due to a perpetual waiting for some divine command from who we surrender to, or as an essential result of His nature (e.g., what if God wants me to surrender everything and just sit perpetually in meditation?). Another friend put it most succinctly: the fear is of a life wasted. He pointed out the fear that in surrendering to a “baba” or guru, he might become content merely imitating or imposing on himself the guru's knowledge, without ever making it truly his own or leaving any possibility for growth beyond it.

There is a common structure to each of these fears. In every case, we imagine a potential reality or life being demanded of us through surrender, which we perceive as somehow lesser or incomplete compared to another reality where the Highest is more fully manifest. We fear that in surrendering, we might fall short of the truly good life, that our surrender will lead to delusion, stagnation, idleness, or an abandoning of our duties.

But we must remember who it is we are surrendering to! We are surrendering to the Highest Good, the Highest Truth, the underlying essence which we have been seeking in all our chasing in every movement of our life. We are not surrendering to some finite concept, a philosophy, a theological system, a pagan deity, spirit, or human guru. If our surrender were such, then indeed, there would be potential for missing the mark. As Sri Aurobindo explains:

However small or low the form of the worship, however limited the idea of the godhead, however restricted the giving, the faith, the effort to get behind the veil of one’s own ego-worship and limitation by material Nature, it yet forms a thread of connection between the soul of man and the All-soul and there is a response. Still the response, the fruit of the adoration and offering is according to the knowledge, the faith and the work and cannot exceed their limitations, and therefore from the point of view of the greater God-knowledge, which alone gives the entire truth of being and becoming, this inferior offering is not given according to the true and highest law of the sacrifice.

For every movement of surrender, there is a response. If we surrender to the joy of great wealth, then we may be led to great wealth. If we surrender purely to a human guru, then we may obtain only his knowledge. If we surrender to a benevolent spirit or deity, we may gain that spirit's will. But if we surrender to God—the Highest—then we will attain the Highest. See now the apparent contradiction in our earlier fear! We worried that in surrendering to the Highest, we might be led astray to a life that is not in accordance with the Highest. But any truth which leads us away from the Highest cannot itself be the Highest. Therefore, let all such fears be put to rest! We surrender to no less than God, the Eternal Absolute, the source of all Good. Any good we can conceive of in a life we see as apart from his path in fact derives its goodness from Him alone.

This kind of thinking can seem to suggest that we should not surrender to God with form, that we should not surrender to Krishna, Durga, or Jesus. But see now that it is precisely because Jesus is God incarnate that we may see him as the target of our surrender. If we see Him as merely a man or great teacher, then He may serve only as a vehicle or guiding light for our surrender, which ultimately is directed towards that which transcends Him. Similarly, Krishna is worthy of surrender only because He is God. The same holds true for any form of God we worship. Even in a traditional guru-shishya relationship, where it can seem we are asked to surrender to a human guru, it is in truth still God that we surrender to, with the human guru becoming the medium for God's guidance. In Hinduism, it is said that God alone is the guru, and all teachings or knowledge we gain from any and all interactions in this world come from none other than Him.

Still, I've perhaps been too quick in dispelling this fear of missing the Highest. Even if we understand that it is God, the Highest, to whom we surrender, we may still fear that we ourselves, in our ignorance, may misinterpret the Highest and thus be led down the wrong path. There are (at least) two responses to this fear. The first is through faith: if God, the Highest, is, as stated in the scriptures and intuited by our hearts, the lover of His devotees, then it is simply impossible that we could long for Him with sincerity, and He would turn us away or allow us to be led astray. As Sri Ramakrishna explains,

So long as the child remains engrossed with its toys, the mother looks after her cooking and other household duties. But when the child no longer relishes the toys, it throws them aside and yells for its mother. Then the mother takes the rice-pot down from the hearth, runs in haste, and takes the child in her arms.

Thus, in truth, we need only to ensure that our longing is genuine. So long as it is the Highest that we surrender to, so long as it is God that we long for, it is guaranteed that our path will lead to Him. Of course, at times in our lives, we may find that though we think we long for God, we are in fact, at a more subtle level, seeking simply the aggrandizement of the ego (see Self-Deception in Spiritual Life by Swami Medhananda). But this simply indicates our surrender is not yet complete, and so the practice continues. But even with the ebb and flow of ignorance, so long as somewhere in our hearts there is a genuine longing for God, our surrender will develop and it will necessarily lead to Him.

But what if we don't have this faith readily available within us? Consider, for example, the Platonist who sees the Good as the Highest and seeks to surrender his life to its pursuit, but does not cognize the Highest as becoming conscious, as having a will in this world, as being the Divine lover of all. I speak from experience, as this was precisely who I was prior to finding God. Here, it is helpful once again to remember who we are surrendering to. We are surrendering to the Highest Good, not to any philosophical system or perspective on the Good. If we surrendered to a specific viewpoint, it is possible our judgement was flawed and we chose a system which does not best express the Highest. However, when we surrender to the Highest itself, we are not necessarily compelled to commit absolutely to some fixed system or worldview which currently seems most promising to us. Rather, our surrender drives us simply to do everything in our power to express the Good in our lives. This kind of surrender compels us to seek advice from those in whom we see the Good manifest, to keep an open mind so that we may uncover our blind spots, and to remain discerning and reflective about the ideas guiding our best attempt to embody the Good. In other words, it compels us to do our best. The result is that our surrender, far from increasing our risk of being led astray, actually by virtue of its one-pointedness, best directs our effort towards the expression of the Highest.

The Concern of Hypocrisy or Uncertainty

With this, I think the fear of missing the Highest in our surrender can be quelled. Not all aversions to surrender, however, take exactly this form. Another fear my friend shared was one of hypocrisy. They worried that they might make the movement of surrender, but then find themselves unable to fully dedicate their lives to God, that their attachments may nonetheless pull them back to the world. They described how, in this scenario, the feeling would be worse than if they had never made the surrender at all. For in the latter case, they would at least have been aware of their ignorance, but in the former they would be fully hypocritical.

The misconception we find here is that the nature of surrender requires a kind of perfectionism. The belief is that one should only surrender once they are entirely free from attachments, once their mind and actions are perfectly aligned and ready to be devoted to the Divine. But this is a misconception of the duty of the spiritual aspirant. We are not tasked with attaining to perfection; that is manifested only by God's grace. Our responsibility is only to place our attachments, our ignorance, our weaknesses, our addictions, all at the feet of the Lord and say, “This is where I am, Lord, but it is You alone that I truly long for.” Sri Aurobindo puts this most beautifully,

Those who aspire in their human strength by effort of knowledge or effort of virtue or effort of laborious self-discipline, grow with much anxious difficulty towards the Eternal; but when the soul gives up its ego and its works to the Divine, God himself comes to us and takes up our burden. To the ignorant he brings the light of the divine knowledge, to the feeble the power of the divine will, to the sinner the liberation of the divine purity, to the suffering the infinite spiritual joy and Ananda. Their weakness and the stumblings of their human strength make no difference. ‘This is my word of promise,’ cries the voice of the Godhead to Arjuna, ‘that he who loves me shall not perish.’

Thus, we may surrender here and now! There is no need to wait until our ignorance is cleared or our failings are corrected. In any case, any progress we make on those fronts is by God's grace alone. We may surrender fully, and it is God Himself who will redirect our tendencies towards Him, leading us from the untrue to the true, from darkness to light, and from death to immortality.

Another form of this same concern questions whether it is even possible to surrender to that which we don't fully know. Of course, the same reasoning as above suggests that surrender should be possible even while in ignorance. But what exactly does that look like? We do intuit that if we know absolutely nothing about That to whom we surrender, then this is the same as having no target of our surrender at all, in which case it is not clear why we should even surrender in the first place. But it is not the case that we know nothing of the object of our surrender! Far from it! We are surrendering to God, who is, by definition, the Highest Truth and the Highest Good. By virtue of this knowledge alone, we can surrender to God, even if we do not know precisely who God is.

Notice that we observe this kind of movement on a smaller scale all the time. Take sports training for example. When you dedicate yourself to following your coach's instructions and training regiment, you may not know every detail of what you're committing yourself to. Nonetheless, you can commit yourself to this process purely on the grounds that your coach is an expert on sports training and seeks to best improve your performance. In the same way, we can surrender to the Highest, purely by virtue of it being the Highest. Knowing this is sufficient because the Highest is what we ultimately seek. We may concern ourselves with ruminations about what precisely the Highest is, but this is only in order to align ourselves with it. Our movement of surrender is not conditioned on this fuller knowing, but is instead what leads to it.

A Clinging to Worldly Desires

Something that may happen as we alleviate all these fears and concerns regarding surrender, is that we may find in the end that we really do “will” something else in the world. We might find that truly we desire something, whether or not it best expresses the Highest. This is a clear instance where, in a very real sense, we will two things. We want the Highest, but we also want to amass great riches. We want the Highest, but we also want a beautiful partner. We want the Highest, but we also want to sometimes let loose, party, and indulge in worldly pleasures. We want the Highest, but we also want to be loved and respected in the world.

Now, this is tricky. On the one hand, as Jesus Christ teaches, “No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and mammon.” As long as we truly will something independently of God, our surrender cannot be complete. Complete surrender requires us to be ready to give up the whole world, including our very being, as an offering at the feet of the Lord. Only when our desire for God transcends all other desires will such surrender be possible. As Kierkegaard, writing under the pseudonym Johannes de silentio, observes,

Infinite resignation is the last stage before faith, so anyone who has not made this movement does not have faith.

So in one sense, it does not seem there is much we can do to alleviate this aversion to surrender. We must simply wait until by intuition, grace, experience, or all of the above, we come to find our longing for God transcends all other desires.

There is, however, one potential misconception we can clear that may bring us at least one step closer to developing this longing. If we see surrender as purely a giving up—what Kierkegaard calls “infinite resignation”—then we only see part of the picture. According to Kierkegaard, complete surrender is a double movement, beginning with a movement of infinite resignation and followed by a movement of faith. Though we renounce our deepest desires, attachments, this entire world and our very being to God, through faith, we know that by virtue of who God is, all that we renounce will be returned to us, transformed and suffused with His essence.

If, as the Hindu believes, God is all that is, then there is nothing we can renounce to God which is not already His (that is not already Him). But when our ego frees up our grip on our conception of the world, we allow God to reveal Himself more fully in all that is. Then we see more clearly in every aspect of the world the role it plays in the fullness of God. Sri Aurobindo further validates Kierkegaard's double movement:

To see nothing but the Divine, to be at every moment in union with him, to love him in all creatures and have the delight of him in all things is the whole condition of his spiritual existence. His God-vision does not divorce him from life, nor does he miss anything of the fullness of life; for God himself becomes the spontaneous bringer to him of every good and of all his inner and outer getting and having, yoga-kṣemaṁ vahāmyaham.

If surrender to God was purely a movement of infinite resignation, then it could be possible that it may “divorce us from life”, but it is through the movement of faith that we see that this surrender in fact returns life to us, transformed into its greatest fullness. We may still amass great wealth, enjoy sweet pleasures, or seek romantic love, but these will no longer be ends in themselves. Instead, they will serve to glorify and remind us of the One who is the infinite enjoyer of all existence, who's essence is pure Bliss.

Still, the Highest can only be attained when all else is surrendered for it. We can only regain the world anew when we first let go of the world as we currently see it. And so, as before, no line of reasoning can make the leap of faith for us. Eventually, we must take that leap ourselves, complete that movement of surrender, and in doing so, we will be led to the One we truly long for.

Jai Mata Di! Jai Mata Di! Jai Mata Di!

References

- The Bhagavad Gita (Sri Aurobindo's translation)

- The Holy Bible (NIV & KJV)

- The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (translated by Swami Nikhilananda)

- Plato's Republic (translated by Paul Shorey)

- Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard (Cambridge Edition)

- Works, Devotion, and Knowledge from Essays on the Gita by Sri Aurobindo