- Published on

A Pragmatic Case for Plato's Unified Form of the Good

- Authors

- Name

- Maa's Beloved

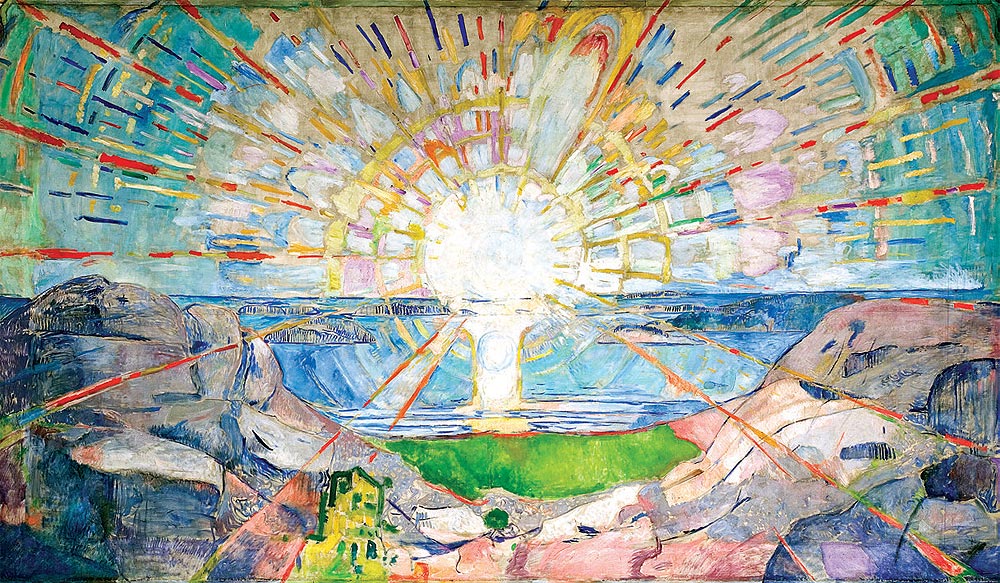

The Sun - Edvard Munch (1909)

The past three posts have been quite heavy, so I'm hoping now to write a shorter post with more immediately practical implications regardless of one's metaphysical beliefs or commitments. In particular, in this essay, I hope to make a pragmatic case for Plato's unified form of the Good (if this doesn't mean anything to you, don't worry. I'll build up to it over the course of the essay!). This post is an essay-form of a 10 minute lightning talk I gave at an event hosted last year by my dear friends Julian and Mariana.

I want to begin with a simple question. Do you have wants? If not, then this essay isn't for you1, though I'm sincerely grateful such an enlightened master has graced my humble blog! For now, this essay is dedicated to the rest of us who do find ourselves wanting. In particular, I'm going to refer to 'that which we want' as our individual good. We all make choices in the world trying, to the best of our ability, to seek our individual good.

But a problem we run into immediately is that we don't actually know clearly what our individual good really is. We don't know what we really want. For example, we may order a black milk tea with boba only to realize what we were really craving was a strawberry matcha latte. Or we may feel conflicted about our wants, and struggle to choose between, say, staying at home to be near family or moving abroad to chase a big opportunity. We may also sometimes think we want something that isn't what we truly want. For example, we may believe that if we just had enough money, we would be happy, and we may devote ourselves fully to this pursuit, only to find that what we really wanted all along was to be loved and understood. To use similar language to Plato, but replacing for now his use of "the Good" with "individual good," he says,

"Every soul pursues [their individual good] and does their utmost for its sake. They divine that [their individual good] is something [(that is, that there is actually something they really want)], but they are perplexed and cannot adequately grasp what it is, nor easily form the sort of stable beliefs about it as they can about other things." (modified ver. of Plato's Republic, 505e)

We each seek our individual good but don't know exactly what it is. The way this typically influences our behavior in the world is that we take a sort of exploration-exploitation approach to things. We simultaneously try to seek our good given our best sense of it at the moment, while also taking measures to learn better what our good is.

But what measures do we have to learn about our good? Well, a couple come to mind quite immediately. For one, we might experiment, trying different things and observing how much joy they bring us. We can also internally reflect and reason about our desires in order to understand them more carefully. We may also engage in practices like meditation which improve our ability to be aware of movements in our mind, and thus possibly become more aware of how our wants arise and what their precise nature is.

But notice that all these methods so far can basically be pursued individually. Another method we use in practice to learn about our individual good is dialogue with others. For example, consider someone in a toxic relationship who believes they're happy, perhaps because they've never experienced healthy love, or because some internal trauma or toxic thought-pattern has made them doubt such love is even possible. This person might talk with a friend, who may share advice, explaining how they, too, couldn't conceive of the possibility of a healthier love while trapped in a previous relationship, but later discovered a love far more fulfilling and joyful than what they had before. The friend might also share tips on how to recognize signs of toxicity in a relationship, or how to notice inner unhappiness that one might be hiding from themselves or trying to repress.

Let's back up for a second. So far, our picture is one in which each person has an individual good that they seek but don't have direct access to, and which they learn about using the tools available to them. But this picture gives no account for how my individual good relates to your individual good. If we suppose that each of our individual goods are fundamentally disconnected or independent, then there is no grounds at all for dialogue to be useful. You may suggest that some idea or direction is worth approaching, but your idea arises out of your pursuit of your individual good. And there's no reason for me to think that the love which is "healthy" for you in accordance with your individual good is in any way likely to be healthy for me too. So in this picture dialogue cannot be used as a tool to discover one's individual good. We are each rendered as fundamentally alien creatures, engaging in interaction or communication only insofar as they directly serve our own individual ends.

Alienation 2 - Zofia Kijak (2012)

Now this obviously feels wrong to us, so something we might try to posit instead is that there is some underlying shared structure to our individual goods, perhaps as a result of us all being human, but that there are also some other aspects which are incidental or arbitrarily unique to us as individuals. While this framing succeeds in giving a reason for dialogue, I will argue that in practice, it also provides a frequently misused escape route which can hinder learning.

To understand this better, I want to make an analogy to the historical development of physics. In some of our earliest stories of how humanity tried to understand this world, we have examples where people would explain natural phenomena by appealing to gods or fate, or to chaos or randomness. Key to these causal explanations is that the causes themselves were understood to be inconceivable or impossible to understand. When and how lightning happens is caused by the gods or by chaos and we can't predict or understand how the gods or chaos behave.

The physicists of course didn't settle for this theory. They looked into the chaos, and found there in fact to be order. Lightning does not spawn arbitrarily, but is caused by a static charge build up of the same sort that happens when we rub our feet on a carpet and poke someone. But this option to explain the unexplainable using an arbitrary random chaos is always available to us. Newtonian mechanics explained much of our world, but there were some anomalies, like slight irregularities in Mercury's orbit that didn't exactly obey the theory. Again, we had the option to explain these anomalies away as caused by the intrinsic noise or stochasticity or unexplainable imperfectness of the world. But we looked deeper and discovered these discrepencies could be better explained and predicted by special and general relativity. Even here we faced anomalies, in particular when looking at the behavior of very small particles. But again, we kept seeking understanding, and developed the theory of quantum mechanics2. This process of course continues.

Now what drives these physicists to keep looking and trying to understand our universe? I believe it is a faith in the possibility of a unified theory of the universe that we can actually understand. Note many physicists may admit that it's theoretically possible that there's some level of reality we truly just can't understand. But physicists refuse to bank on this as a resort or a reason to stop seeking a deeper understanding. They hold onto their hope. This is because if they assume the universe can be understood, and it turns out it cannot, they just waste time, but if they assume some part of the universe cannot be understood or that it is simply arbitrary chaos, and this is in fact not true, they miss out on a deeper understanding of their reality.

Now, if we are worried about missing out on a deeper physical understanding of our reality, how much more should we be concerned of missing out on an understanding of our own good! Returning to using dialogue with others in pursuit of understanding our individual good, if we begin with this framework that our individual goods are in some sense connected, but also have an arbitrary cause that leads to diversity, then if we're not careful, we may use this arbitrariness in the same way chaos can be used to explain away relationships we have not yet understood. For example, if we speak to someone about the understanding they have obtained so far about their individual good and the tools they've used to do so, but we find it too alien to understand yet, perhaps because they come from a cultural or lived background that we can't yet connect with, we can simply say, "Oh, this must be the part of the individual good that varies arbitrarily from person to person," and so any reason to delve more deeply into the other person is assumed away.

Here, I make my pragmatic case for the Platonic Form of the Good. As opposed to this model where we consider individual good to be in part structure and in part arbitrary, we, like the physicist, have faith in the possibility of a unified theory of the Good, that explains the development of not just my own good, but also that of every other person.3 In light of this hope, when we encounter someone with an understanding of the Good that is difficult to understand, we won't rush to explain it away as simply due to us being different, but will instead seek to understand how such an understanding of the Good emerges out of the person's experiences, personality, and understanding of the world. We will aim not only to uncover the hidden wisdom in the other's understanding, but also to understand the specific forms of ignorance, distortion, or trauma that give rise to their mistakes. Crucially, these mistakes won't be grasped simply by imposing our own conception of the Good upon them, but by identifying the tensions and points of dissatisfaction in their own pursuit of the Good, which is in essence the same pursuit as ours.4

This view also opens up the possibility of a humanity level "science" of the Good, in which we all work together to understand our Good better. I believe the history of philosophy and religion can in fact be seen as man's collective attempt to do this. In the west, the stream of thinkers devoted to understanding the Good have included Plato, Aristotle, Jesus Christ, Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, Locke, Kant, Spinoza, Hegel, and so many more. In the east, it has included the ancient Vedic Ṛṣis, Sri Krishna, Veda Vyasa, Gautama Buddha, Lao Tzu, Shankaracharya, Ramanuja, Madhvacharya, Abhinavagupta, Guru Nanak, and again many, many more. Beyond philosophers and religious thinkers, humanity has also sought to explore the Good through literature, poetry, painting, music, drama, dance, ritual, and all kinds of other mediums of human expression.

And I believe, as with physics, we are not yet done. Just as physics still faces the open problem of reconciling quantum theory with general relativity, the study of the Good is filled with open problems. We have yet to understand the relationship between the wisdom of the east and that of the west, and a true synthesis is yet to be obtained, though I believe a compelling attempt at a synthesis has been made in the work of contemporary Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo. We also have yet to completely understand how modern scientific developments in theoretical physics, chemistry, biology, psychology, etc. interface with or influence the extensive philosophical study of the Good. These two cannot sensibly be seen as independent, and so we must seek a unified explanation of both. Finally, we as humanity are still recovering from the traumas of the ways in which degenerated forms of religious traditions or philosophies of the Good have resulted in widespread harm, dogmatism, and hatred, so it remains to be more fully understood what this tendency towards degeneracy is, why it exists, and how we may, as my friend Mariana once asked, learn about our world, our self, and our Good without harming others on the way.5

Footnotes

Barring the case where you think you don't have wants, but in fact do. Then this essay is especially for you, haha! As I've brought up in previous posts, this kind of self-deception is very common in spiritual life, where we think we are fulfilled, but our wants have just become temporarily dormant or hidden, in which case we're often in for a rude awakening when they suddenly reappear with great force. I have personally experienced such a moment in a time when I felt I was free of most obvious attachments and had a deep one-pointed longing for God (ah, the naivete..), only to find that in a period of severe illness and fatigue, in which my prana / life energy were taken away to such a degree that I could hardly find energy to even meditate or pray, that I had come to resent the very God I loved. My attachment for prana or having great energy for work and service was dormant when I was full of prana, but rose with such strength when it was gone that I turned in resentment even from the God whom I love! ↩

This quick gloss over the history of physics is almost certainly grossly oversimplified, but I believe this process of noticing places where our existing theories don't exactly match what we observe and seeking deeper theories which explain these discrepancies is pervasive throughout the development of physics. ↩

For this essay, I'm focused particularly on this faith in the possibility of a unified understanding of the Good, but I believe this analogy to the physicist's faith reveals many other forms of faith that guide us in our lives. Another such example is the faith in the possibility of some kind of goodness latent in every being. It is theoretically possible that there are some people who are truly evil through and through, but many religious traditions call us to believe in the essential inner goodness of man, so that even when we see outward evil, we, with hope and empathy, keep looking for the inner goodness which has been repressed or covered up by trauma, ignorance, or darkness. In Reconciling Sin and Avidya, Part 1, I further explore the theological grounding for this belief in the Hindu and Christian traditions. ↩

Importantly, this doesn't imply that the way the Good manifests in everyone will be the same, or that pursuing the Good leads each person toward a single, completely uniform ideal. Rather, the Good is clearly always mediated through one's temperament, capacities, and life experiences. In this way, some may be called to pursue the highest and most complete knowledge; some to be strong and protect the vulnerable, or fight for revolutionary change; some to care for and sustain their families, businesses, and local communities. Some may be called to be monastics and others householders. It also means people will embody and communicate the Good in different ways, through distinct ways of teaching and learning, different modes of relating to others, varied senses of humor and emotional expression, and different relationships to God, spirituality, or meaning more broadly. But the claim here is that it is one unified Good which takes all these expressions in these different contexts, and the practical import of the hope in this possibility is the belief that by understanding how the Good takes form in another, we may come to better understand how it takes form in us. ↩

Some might argue, I've not fully made a case for Plato's theory of a unified form of the Good. Plato further adds in the metaphysical belief that this Good exists as a real form outside of us, and any sense we have of the Good is a fuzzy and incomplete perception of this form. But my aim in this essay is not to put forward any major metaphysical claims about the Good, but to present the value in holding to the possibility of a unified theory or understanding of the Good. This value holds regardless of whether the Good is an external form as Plato posits, or is intrinsic to our form as human beings as Aristotle says, or is the Christ as the underlying Logos of reality itself, or is the truth of Being or Consciousness itself as posited by Vedanta, or is simply patterns in our biology arising out of our shared evolutionary history. ↩